How Design App For Happiness

Designing Happy

Building a product to further a basic human emotion

![]()

The origin story

All good startups have one: an origin story. In this case, our Founder and CEO, Jeremy Fischbach, was going through a bit of a rough patch to say the least. As he puts it:

It was a rainy summer night in New Orleans in 2015 — one of the most difficult years of my life. My last endeavor, a psych-tech company dedicated to helping people explore their inner realms, was on life support. A relationship I cared deeply about was, too. And that mixture of commitment and belief that fuels start-ups and relationships was gone. My co-founders and I were too defeated to support each other through the last chapter of a failed start-up, and the woman I loved deeply was too hurt by me, and I was too hurt by her, for us to comfort each other without cringing.

And as I'm sure has happened to all of us at one point in our lives, Jeremy didn't have anyone to turn to. Well…he did. He had plenty of close family and friends, but none that could support him exactly when and how he needed.

Time and time again I struggled to reach the people closest to me when I needed them most. And when I was fortunate enough to get a friend or family member on the phone, I couldn't bring myself to ask for the thing I wanted most — for someone to listen to me, comfort me, encourage me . . . to remind me that they cared about me.

In time it became clear to Jeremy what he was missing in that moment, and had indeed been missing for a long time: real emotional support.

A basic human problem

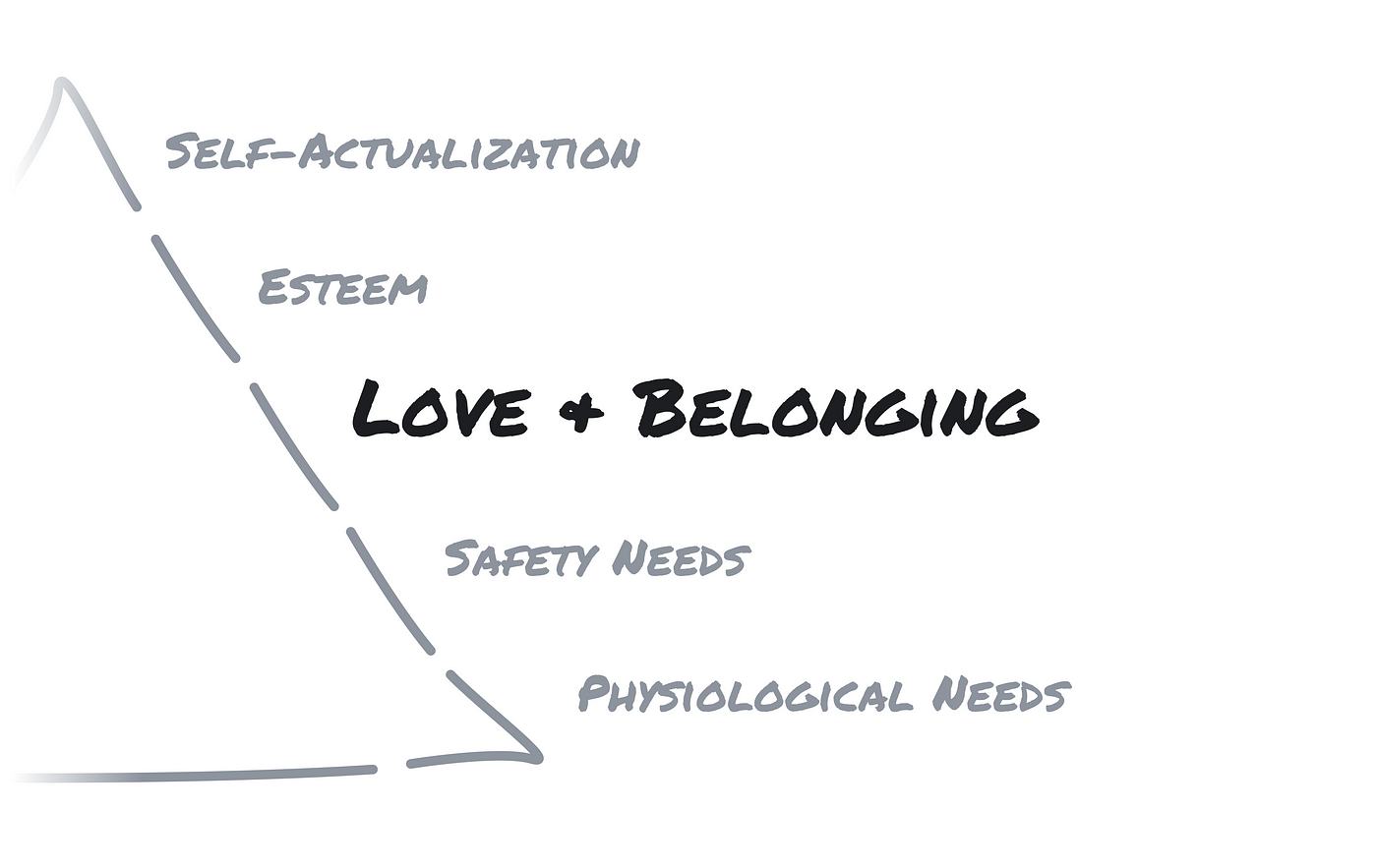

It becomes clear to many of us at a very young age what we need to survive: food, water, sleep and shelter. You're probably picturing and trying to recall the various striations of Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs. Let me help you out here:

While most of us are quite adept at achieving the bottom two layers of this pyramid, physiological needs and safety, it turns out the middle slice, love and belonging, is a bit less attainable and serves as a gatekeeper to esteem and self-actualization. While most of us, like Jeremy, have a close group of family and friends who are in theory always there to support and nurture us, in practice it often doesn't work out that way.

The times when we need support the most are often the same times when it is least available to us.

They are either busy or distant when we need them or we ourselves find it difficult or impossible to ask them outright for the support we need. If this sounds foreign to you, then you're in the minority as it turns out.

Americans aren't getting the emotional support they need:

40 million Americans report that they are chronically lonely and 52 million Americans report feeling extreme stress.

H ealth problems stemming from stress and loneliness include: obesity, high blood pressure, alcoholism, depression, heart disease, insomnia, and stroke.

The solution

In surveying the landscape, one might think there are already solutions for this problem including traditional mental health solutions as well as new up-and-coming behavioral health startups. Newer solutions often require high levels of customer commitment for efficacy (e.g. Lantern, Joyable, Headspace) or replicate an older model with new technology (e.g. Talkspace, 7Cups, Crisis Text Line, 1docway). Traditional methods, like therapy, psychiatry, and crisis hotlines are often expensive, inconvenient, stigmatized or for extreme situations.

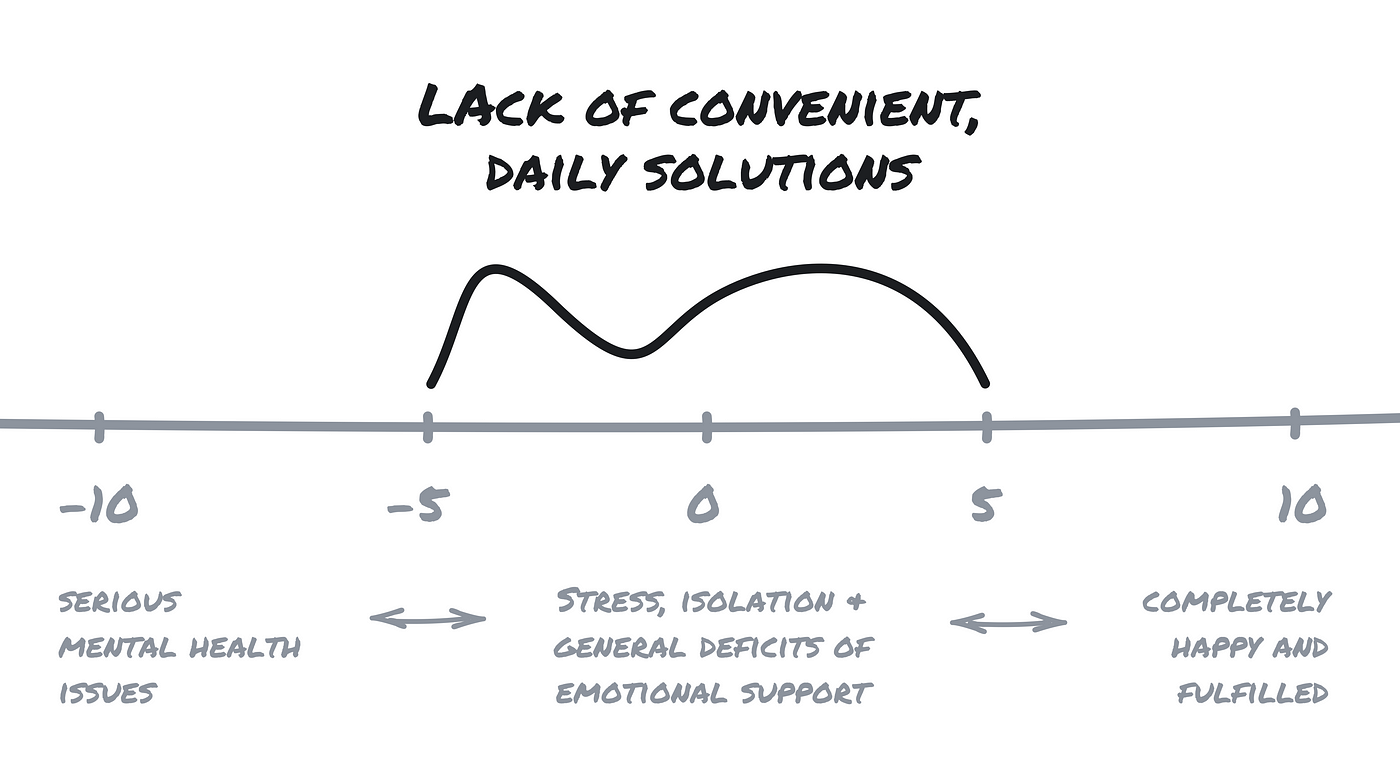

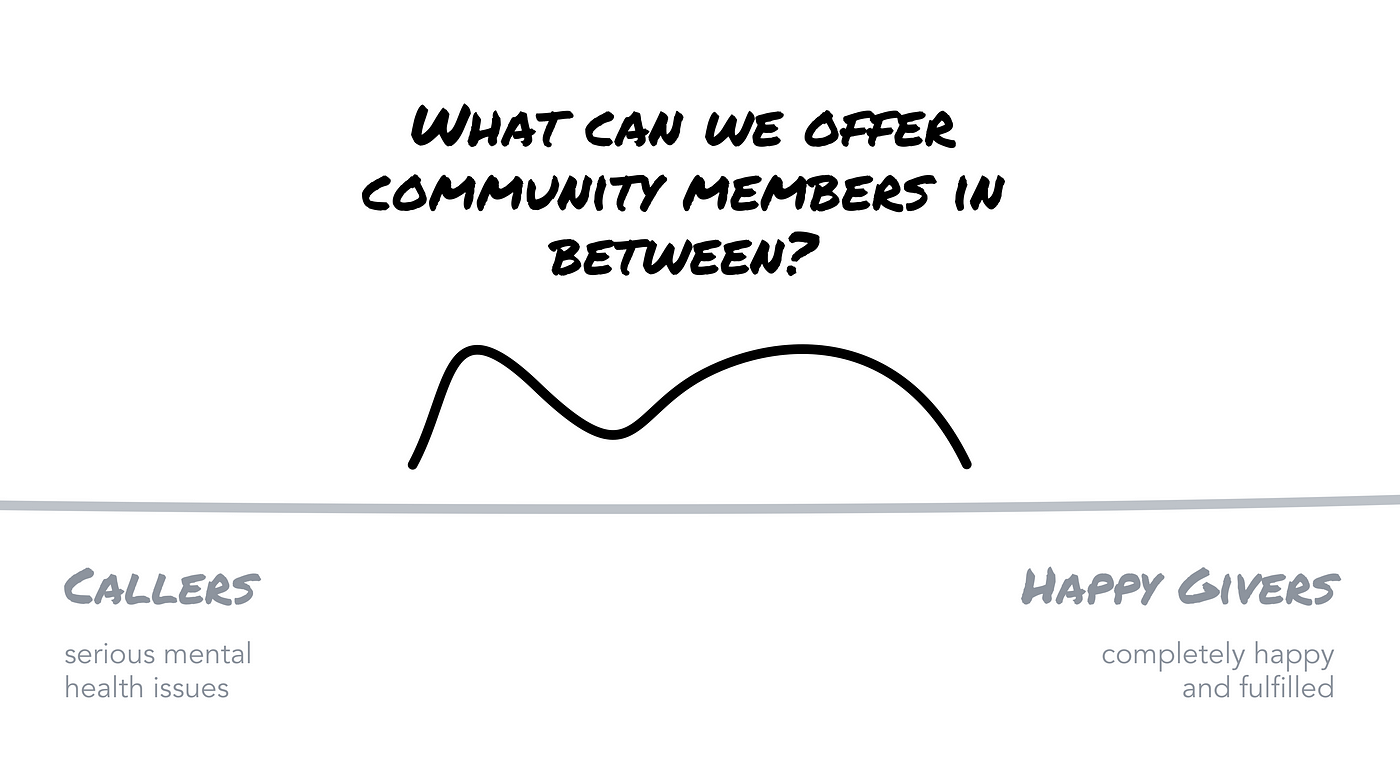

Think of mental health as a scale from -10 (serious mental health issues) to 10 (completely happy and fulfilled). The traditional solutions for mental health issues are well suited for the far left of the scale, while the far right lacks any need for a solution. It is the -5 to 5 range, characterized by stress, isolation and general deficits of emotional support, that is lacking in convenient, daily solutions.

With this in mind, our goal was to create a product that destigamized the sharing of ones thoughts and stresses with a total stranger, on a consistent basis, over the phone. Clearly this is sort of a ridiculous goal. But so was expecting people to feel comfortable hopping in a random persons car and getting out without handing over money.

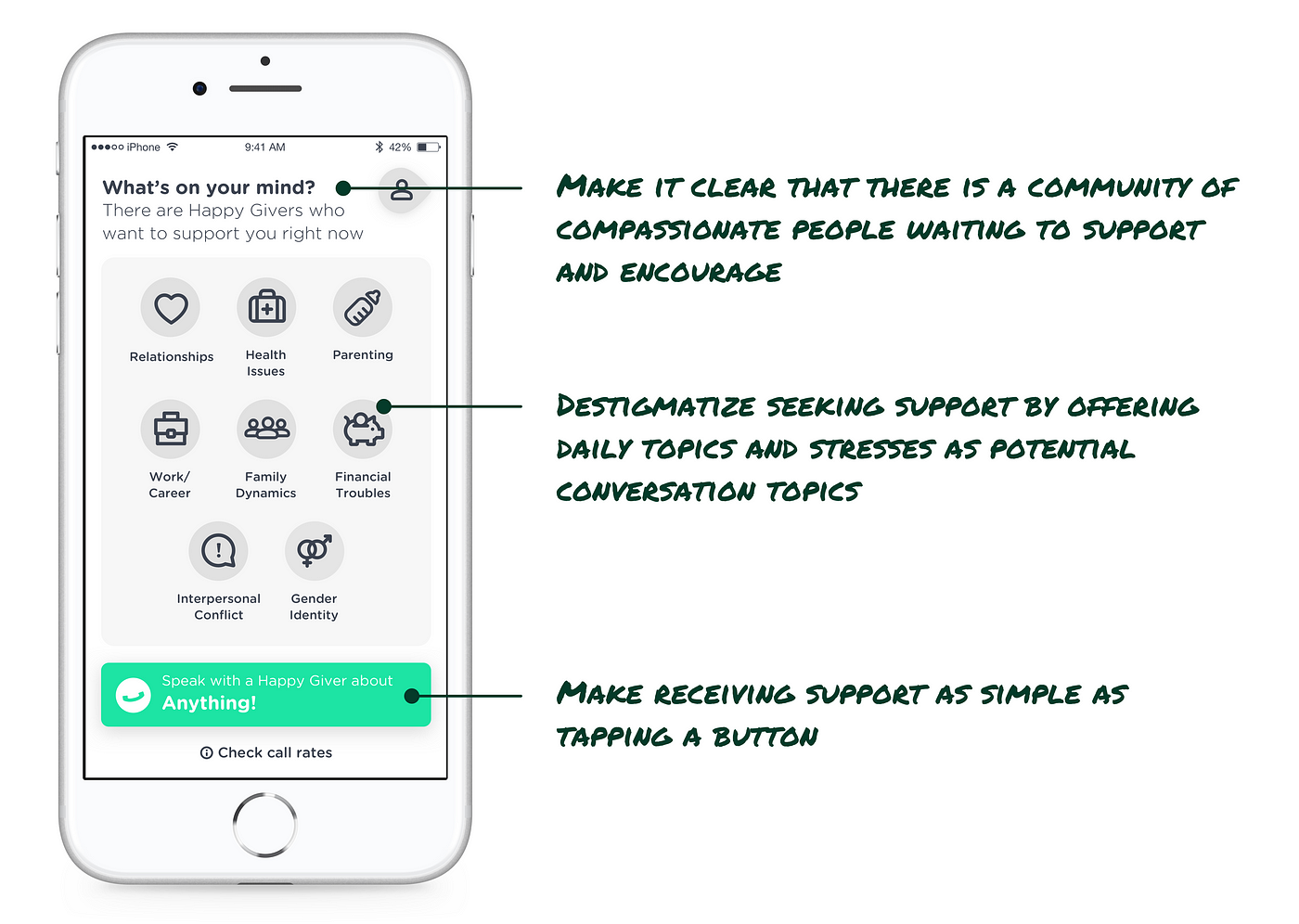

So we built Happy, an app where people can access emotional support — attention, compassion, and encouragement — on demand, over the phone. Happy connects callers with everyday people who have proven themselves to be exceptionally good at supporting others; we call them "Happy Givers".

We hypothesized that we'd accomplish our goal by adhering to a few tenets.

First, we needed to make it clear that there is a community of compassionate people waiting to support and encourage you. By making it clear that there is a whole community of people, we figured we'd soften the blow of talking to an absolute stranger and make it clear you are not the only one seeking support.

Second, in order to destigmatize seeking support, we wanted to offer examples of daily issues and stresses as potential conversation starters. These make it clear that (a) you're not the only one going through these issues and in fact they are quite common, and (b) our Happy Givers are equipped to discuss these topics. In our early research, we discovered that without these options, starting a call felt too nebulous and the fear of "what will we talk about" was great enough to deter the call altogether.

Third, and this is the simplest one, make receiving support as simple as tapping a button. Life is hard enough, hell that's why people need this support. We didn't want to make seeking it difficult too.

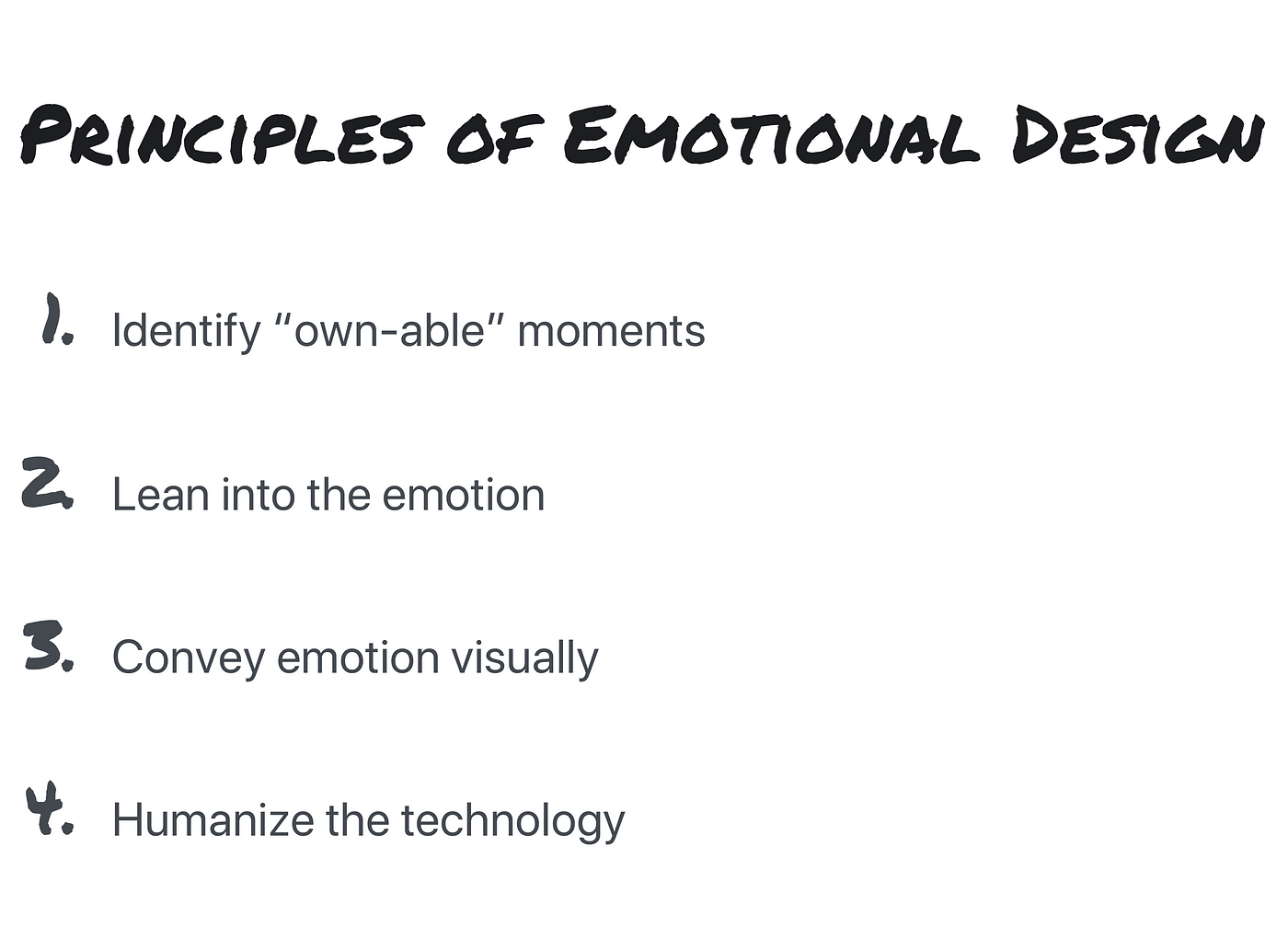

There was clearly a strong emotional design aspect to this project. Our thinking was as follows (based on the Principles of Emotional Design work and conference talks I have previously given):

1. Identify "own-able" moments

The moment we identified was the culmination of stresses and worries that leads a person to download the app. We moved the button to make a call as early in the process as possible and removed the "pain of paying" by making the first call free. Our hypothesis was that if a user could experience a call and talk to one of our supportive "Happy Givers" they will keep coming back.

2. Lean into the emotion

Instead of shying away from the reason why someone is opening the app, we offer up potential and likely reasons. Our hypothesis is that by simply offering reasons why people might call in, this might destigmatize those reasons and the associated emotions and set the expectations for the call they will have with a Happy Giver.

3. Convey emotion visually

The light-hearted color palette, playful icons, and subtle animations make the entire experience feel less intimidating.

4. Humanize the technology

This one was particularly hard. By nature, this product is a perfect juncture of human and technology, but conveying the human aspect was the hard part. We'd love to make it clear who you'd connect with but this is technically difficult and not necessarily a good thing from a human bias standpoint (a man might have reservations about speaking with a man about his problems, while it might have no correlation with the outcome of the conversation). We threaded the needle by making it clear that there is a vast network of compassionate individuals, but not letting you know beforehand who you'd be connected with, as to avert those inherent biases.

Here is a quick glimpse of a key moment in user experience that brings together our product tenets and the Principles of Emotional Design:

Early pilots of this product yielded the following results:

94% of callers reported a significant increase in happiness after using the service

There was a 42% average increase in happiness and 54% increase in calmness

90% of callers want to use the service regularly

Beyond the App: The Movement

Like most companies and entrepreneurs, we fell in love with the problem: providing support to our lonely teens, anxious college students, stressed parents, neglected veterans, and lonely grandparents.

Our first attempt at solving this problem, as previous discussed, was an app. We thought it would amazing if, in the moments when life brought you down, or you simply wanted to connect with a caring person, or hear a few words of encouragement, you could connect, at the push of a button, with one of our compassionate community members.

The app quickly turned into a community with thousands of excited and mobilized Happy Givers, months even before the app launched. But we soon realized that we were only catering to the edges of the community.

This became particularly clear when our CEO, Jeremy, spoke at his alma mater, Princeton. He gave a series of talks about Happy and the community and movement it was creating. Without fail, every single attendee would voice their excitement and willingness to get involved. However, this would lead to close to zero callers or new Happy Givers.

We were offering support for those who needed it enough to call, and the ability to support others, for the most compassionate people, but nothing in the middle. It was all or nothing.

Our current working hypothesis is that we should offer a spectrum of actions a user can take to get and give support. We should also offer a consumption surface with the sole purpose of making you happy and filling that void throughout the day and week.

With these things in mind we have begun designing the next version of the app, which we believe will support our transition from an app, to a community, to a movement.

Shoutout to the team:

Jeremy Fischbach, CEO

Ely Alvarado, CTO

Ash Sarohia, CFO

Matt Rogers, Product Design

Kristan Toth, Head of Operations

Cheyenne Quinn, Outreach & Partnerships

This story is published in The Startup, Medium's largest entrepreneurship publication followed by + 379,938 people.

Subscribe to receive our top stories here.

How Design App For Happiness

Source: https://medium.com/swlh/designing-happy-b6400f6f1321

Posted by: irvinhaster.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Design App For Happiness"

Post a Comment